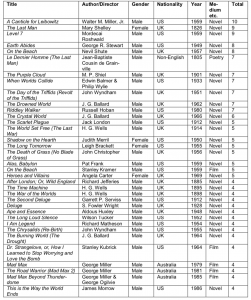

In a very interesting paper entitled « Keeping count of the the end of the world », Jerry Määttä provides an insightful statistical analysis of fluctuations of anglophone apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic disaster narratives. This post is less interested by the final results, i.e what does these fluctuations tell us about society, but more about the research approach which is key in our opinion.

First of all, a statistical analysis is done with a database that has to be as representative as possible of the genre. Instead of taking it upon himself to list all apocalyptic narratives, the author chose to do a meta analysis. This is done by selecting a number of monographs and anthologies. The underlying idea is that if researchers who are inherently limited to a few number of pages discuss a movie or a novel, they can be considered to be important and influential. The idea is extremely interesting and indeed greatly facilitates the amount of work needed in order to get a hold on a coherent list of sources when analyzing imaginaries. Nevertheless, it raises the issue of « Important and influential ». In a following post we have discussed the feedback loop that we are looking into when analyzing imaginaries : people watch movies, get a sense of future from it, and start building it, these technologies then being shown in movies and so forth. So we could consider that influential works are the ones that have the greatest potential of starting that loop, which would be in line with Määttä’s approach. The question that has to be raised here is wether the people who are trend setters and tech engineers are keen on watching the « Important and influential » movie. So far, we do not know of a work that has analyzed that aspect but we get the feeling that this type of personalities might be looking in more counterculture, geek and specific imaginaries on top of the usual stuff that everybody watches (if they watch it at all in fact).

« The imaginaries are key, but knowing what are their audiences seems to be as important in order to analyze them. »

The other aspect that is very interesting is how relatively poor these important imaginaries are. When the authors focuses on the 35 works that have been quoted by four studies or more, the kind of disaster depicted are not very diverse. The nuclear wars and aftermaths accounts for half of the works, followed by diseases (fifteen per cent of the works). The remaining ones have more « innovative » disasters such as celestial phenomena or aliens encounters. This analyse leads us back to the precedent paragraph : by selecting important imaginaries, are we not limiting ourselves to what will fit with the public and critics’ needs of the time, thus limiting the creativity and diversity of the works that are analyzed ? This raises a second issue : what about the way we categorize content? Looking after a kind of disease could obviously lead to a rather conservative issue, given the the fact that the amount of historical points of references are rather limited. Maybe the way some disease occur (planned, unplanned, in a war, etc.) or also the way humanity reacts might be a more fruitful filter of analysis. Or, to be clearer : there is value at finding non conventional ways to make clusters out of imaginaries.

The author perfectly summarizes when he writes that « it could also be argued that it is often during periods (and in social, political, historical contexts) when there is an increased need for these kinds of stories that authors and directors produce them in unusually large numbers, or even that it is only during these periods and their specific Zeitgeist that certain works manage to make lasting impressions and become minor classics (sometimes almost regardless of perceived aesthetic qualities), both of which would seem to suggest that examining the contexts of the consecrated and memorable works of the genre might in fact be seen as at least partially representative for the popularity and impact of the whole genre ». So limiting analysis to mainstream and popular works might only show (at least partially) what the context of the moment is. Just as there are some trends regarding counter culture (aka dystopian ecological future right now or the cyberpunk trend years ago), the question of how to define and find actual counter culture before it becomes fully integrated into mainstream pop culture is another challenging point of method.

The last point that we find of interest if the analysis that Määttä makes by comparing the number of productions in novels and films. What he is doing is comparing the evolutions between them and he tries to explain why we can see some differences. But the most interesting point to us (even though an obvious one, it can still be underlined) : much more novels are published than movies. Beyond the obvious, this raises the question of the quality of the medium that is investigated and the power of each for the feedback loop. The fact that there are so much more novels underlines that it is the place where we might find the more diverse and unexpected ideas. Obviously, the films are better at immersing people and visually showing how a technology could work, but the sheer differences in numbers pushes for a prioritization of analysis towards novels. We will discuss the power of each imaginary later in an other post.