Humanity has always tried to predict its future. However, upon closer inspection, many techniques turn out to be more aimed at solving problems for today, rather than at making reliable predictions of the future. Both the profusion of techniques and this ambiguity in their actual effects are found in contemporary speculative practices.

These two aspects therefore make it difficult to evaluate the tools we have at our disposal today to work on the future. All the more so because the success of these approaches is difficult to evaluate: one must precisely wait for the future to come before judging; and the primary effect of prediction is to modify behavior and thus to favor its realization, or, on the contrary, to prevent it. And the numerous failures of predictions do not fail to call into question the relevance or even the possibility of “serious” foresight. One may therefore wonder if the future of speculative approaches is not to disappear? Or, perhaps less empathetically, what are the future forms of practice at a time when we seem to be observing a return to the future, after a generation or two devoted to deconstructing the positivism of the Glorious Thirties and the ideology of progress that gave birth to it.

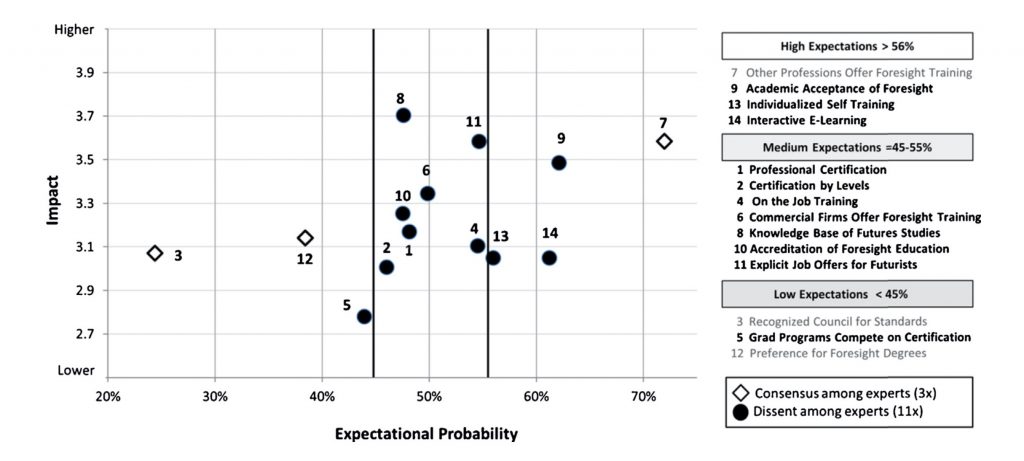

This is what three researchers from Virginia Beach and Nuremberg tried to do in 2015. Using the Delphi method as they should, they tried to imagine what the territory of foresight might look like in the coming years. Their reflections led them to point out the question of the certification of professionals as a critical issue. Indeed, like any expertise, it raises the question of defining what can be decently certified, between mastery of the tools or validation by a recognized learning path?

Five years after this assessment, have we made any progress? The answer is no.

To begin with, and in coherence with the Delphi method, the researchers carried out a literature review and interviewed experts and practitioners. From this material, they extracted 14 projections meeting the method’s “standards”. The opposition between academic certification and individual training structures most of the defined trajectories. The testing with experts, still within the framework of the Delphi method, allowed a focus on three prospective scenarios aiming at detailing in a more narrative way the evolutions to come: assimilation by other professions, academicization of the profession, and finally certification.

These scenarios are developed on the basis of each of the analyzed trajectories, the arguments being weighted and discussed through an analysis grid highlighting the “Inhibitors” and the “Enablers”.

According to the research authors, the assimilation scenario seems to be the most likely. It would imply that professions engaged in projection and speculation practices would find themselves digesting the techniques of foresight and offering specific certifications to practitioners in their own field. In other words, a certain part of foresight would be assimilated into other fields of professional activity, whose certification would then be subject to criteria external to foresight itself.

In fact, this process of absorption of a set of methods and techniques by a new discipline is quite ordinary in the contemporary dynamics of the professional structuring of expertise. If we limit ourselves to the field of innovation alone, marketing has absorbed a good part of the social sciences – social psychology first, sociology and anthropology second – or design has taken precedence over ergonomics in the mastery of product design and digital services in particular. Beyond the challenges of professional recognition and the corporatism that this can generate, this process implies a second challenge: that of transforming concepts by moving from one universe to another. It is currently very visible on the part of designers who resist the methods of design thinking with the double argument of a loss of corporatist mastery (and the idea that there would be no good design thinking without designers) and a risk of degradation of the quality of the design activity in this context (with the argument of a loss of capacity for divergence or a low level of tangibilization activity in this managerial version of design).

Detail of the proposed scenarii

More or less, we hypothesize that the prediction thus proposed is realized in the field of design fiction and the myriad of speculative design practices, the tools of prospective being absorbed, and transformed, by their practice through design. At the price of what transformations? This is the question we think it is useful to ask.

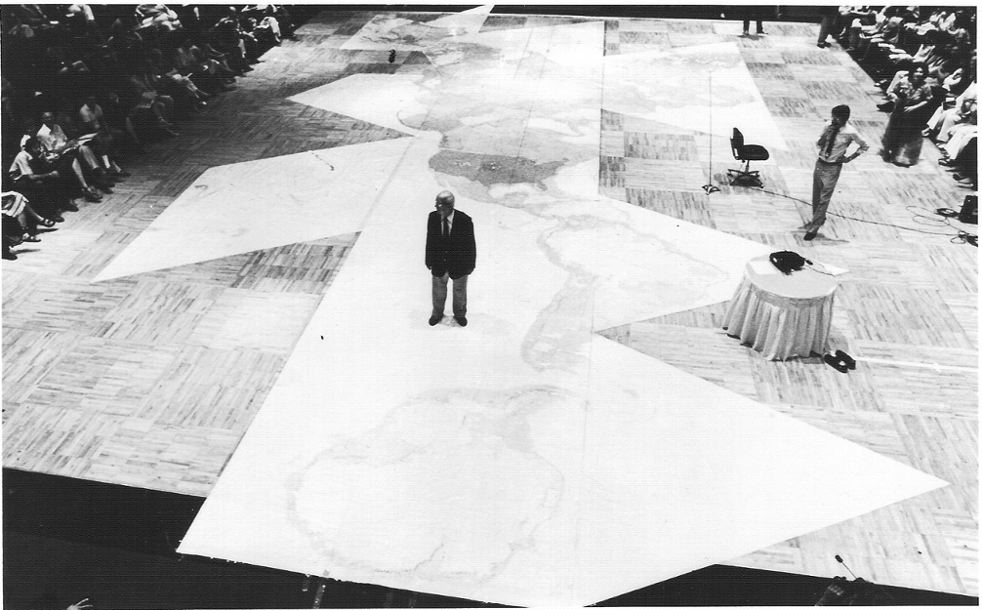

- The first transformation we point out concerns the predictive character of foresight. From this point of view, the “classical” approaches to foresight (from Rand and Shell, see the work of Jenny Andersson at Sciences Po) are the children of a techno-enthusiastic period when it was thought that we could model sometimes complex elements and, above all, be able to orient future futures. The work of researchers such as Fuller and his Dimaxyon map is a perfect example: the idea was to try to model the planet (as “spaceship earth”), and on this basis, to deduce options for living together. However, unlike the work which, like the Club of Rome, speculated within a fixed framework, Fuller advocated an experimental approach aimed, with his teams and in countless workshops around the world, at testing and inventing systems capable of meeting the challenges of a preferable future, particularly in terms of energy resources. In this sense, the ability to predict was compatible with a constructivist approach to the future. However, speculative design stemming from design is part of another tradition, that of criticizing the world. Perhaps because of a certain unease with its history intrinsically linked to industry and capitalism, prospective design today seems to be largely following the path of a critique of what gave birth to it, and moving away from positively predictive attempts.

- A second possible transformation concerns the conditions of tangibilisation of the future. In this respect, Fuller’s exercises are more the exception than the rule in foresight. Through its capacity to make and experiment, design offers a field of speculation that is largely new to foresight, in various respects: modelling means giving oneself the means to discover blind spots in the reflection that are revealed through use; it also means making possible other forms of collaboration with various audiences; and finally, it means opening up to forms of speculation in action carried out by a great many individuals outside the field of foresight, and thus benefiting from a form of distributed intelligence that it is possible to federate.

RGH Fuller’s World game series

- The third transformation that we identify is finally related to the certification issues that we discussed at the beginning of this article. As soon as it enters design schools, what criteria should be put forward to make the design fiction approach grow? The time seems opportune, perhaps in order to better balance the different origins of this approach, despite the victory (? completed?) of design over foresight.

The subject is critical, and naturally complex, just as design is a multiple profession. Rather than focusing the debate on the diploma and the origin of the profession, it seems useful to us to put the practice itself back at the center. And to ask ourselves how can we enrich prospective without abandoning its specific contributions? In doing so, we should ask the question of its impact and go beyond a practice which, too often in our opinion, continues to be satisfied with posing a critical framework to justify its success, as if the means were an end in itself or, even worse, that the impact on reality was necessarily aligned with the method.

Working on the conditions of quality in design fiction therefore seems to us an interesting exercise. To introduce it, we see two first propositions:

- Decentralize. This means first determining what the center is. This involves purging the utopias and dystopias most present in our environment. Concretely, this means producing a cartography of all the “traces” of the future that we need to master in order not to reproduce them. Or else, if we do it, let it be voluntary and with a clear methodological objective.

- Think symmetrically. Among the recurring biases in work on the future, that of technocentrism is perhaps the most common: considering that tomorrow is a technological extrapolation of current data. And this without thinking about the social consequences, especially the unexpected ones. For example, thinking about mobile telephony in the early 2000s would have meant trying to imagine its positive application during voting in an African democracy (positive), but also the privacy issues (potentially negative). However, by dint of wanting to get out of this techno-centrism, some actors focus too much on the social dimension, almost forgetting the technological evolution. This is the case of so-called critical fictions that explore the risk of data and information control within totalitarian universes which, since 1984 at least, have all looked alike, borrowing the figure of a Stalinist Soviet model. A model that is detestable, by the way, but which encloses the posture in a hundred or so agreed-upon criticisms. This is what leads us to think that any creative reflection on the future must be symmetrical and play on both technical and social developments, without subjugating one to the other. This in the form of multiple scenarios prioritizing one aspect and then the other.

These are the first two steps. We invited the reader to continue as we did. And, in so doing, enrich and strengthen the design fiction toolbox by making it walk on its own two feet, foresight and design.