So, to be honest, this article is not really about our imaginaries (not at all in fact), and is rooted in economics theory. It has been a while since Nicolas has dived into that, but we still believe that it can bring food for thought on this blog, and we will try to explain why. Also, just as a disclaimer, we are making up the groundhog paradox with this post :).

Since Adam Smith, economists have been extremely interested in the way humans make inter temporal decisions. i.e, how we decide to do what, how much of it, and at what time ? The basic idea here is that we value more having a desert now than we do having it next year. Said in economics’ words, we discount the pleasure we will have from future consumptions. Since the economists believe that we are purely rational beings, this has led to quite some discussions, Mr Pigou famously writing in 1920 that « our telescopic faculty is defective and … we therefore, see future pleasures, as it were on a diminished scale ».

In order to address this « defectiveness », economists have tried to create explanatory models. The first one was made by Fisher who used indifference curves in order to show how someone will make a choice between now and the future, and this based on the market’s interest rate.

Some indifference curves based on Fisher’s approach.

This is obviously a theoretical model, but interestingly enough, aside of this classical model, Fisher was the first one to highlight a key aspect of inter temporal choice, which is that the discounting will depend on an individual’s level of income: the poorer you are, the more you will value current consumption.

Samuelson then proposed the first clear version of a discounted utility model. The maths are super simple and basically say that if I value a desert 100 now, and 90 in a year, I have a 10% utility discount. Obviously, it is so simple that every economics researcher on earth jumped on it, forgetting the « serious limitations » that Samuelson raised in the conclusions of his paper, and mainly the fact that the rate might change over time with people being over-biased towards immediate rewards.

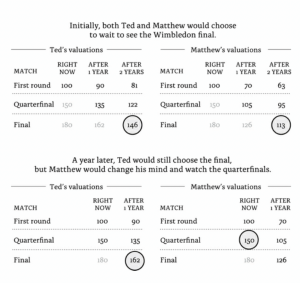

Thaler has given a very good example of this issue in his book (amazing, a must read!) by explaining the difference between someone who uses an exponential function for discounting versus someone who uses a quasi-hyperbolic function for discounting. Considering a great tennis match to come, he proposes that Ted has a fixed rated of 10% discounting. So, if the match is valued at 100 this year, it will be valued 90 the next year, 81 the second, 72 the third etc. As opposed to Ted, Matthew discounts everything that he has to wait a year to consume by 30%, the next year at 10%, and then he stops discounting at all (which is a quasi-hyperbolic function). Obviously, each of them has to wait for the second year to go to the quarterfinal, and the third year to go the finals.

For each of them, the valuation for the first round is 100, the quaterfinal is 150, and the final is 180. Keeping in mind each person’s discounting, this is the choices that we get, and, as we can see, the results differ quite a lot.

Misbehaving, Tahler R. (2016)

Based on these approches, economists have developed more and more developed models, that tried to explain how people behave during their lifetime. Yes, we suppose here that people are smart enough to rationally think about their whole life’s consumption, savings, risks etc. The most renown model is the Modigliani lifecycle hypothesis that basically states that humans are capable of making perfect assumptions regarding how much they will make during their life, when, how long they will live and of course … since we are rational, how to manage all this. Tahler also underlines that the model implies that wealth is fungible : the value of a house is equivalent to the same amount being available in cash.

You do not need to be an economist to understand that all these assumptions are limiting and that this is obviously fairly far from what we all live in real life.There are numerous works being done right now on how humans behave and deal with these uncertainties in order to develop more adequate models. As an example, Thaler (yes, him again) challenges the idea of fungibility by proposing the behavioral life-cycle hypothesis. This model proposes that money is not fungible, hence that winning 1.000$ at a lottery of increasing the value of a retirement plan by the same amount does not have the same impact.

To conclude this post, we can say that we basically do not know how to model the way people value things, plan their future, and react to variations in their hypothesis. And as shown, economics so far only offers a limited range of answers to these issues.

Also, and that might be a key conclusion here, the Matthew and Ted examples show us that, depending on the way we discount the future, the future might be an everyday “today”. Put differently : the way I value my future consumption in 2025 being different from the way I will value it tomorrow, it is highly complicated to projet linear data as we usually do in futurism. So discussing about the future might be more efficient if we admit that the future is a succession of « todays », and that we should only imagine those « todays ».

Which might be quite a change in perspective.

Featured image : Groundhog Day w/ Bill Murray